In an unprecedented move, South Korea’s top universities are starting to deny admission to applicants with records of school bullying even when those students have outstanding grades. This marks a major shift in how character and past behavior are weighed alongside academic achievement in the nation’s highly competitive higher education system.

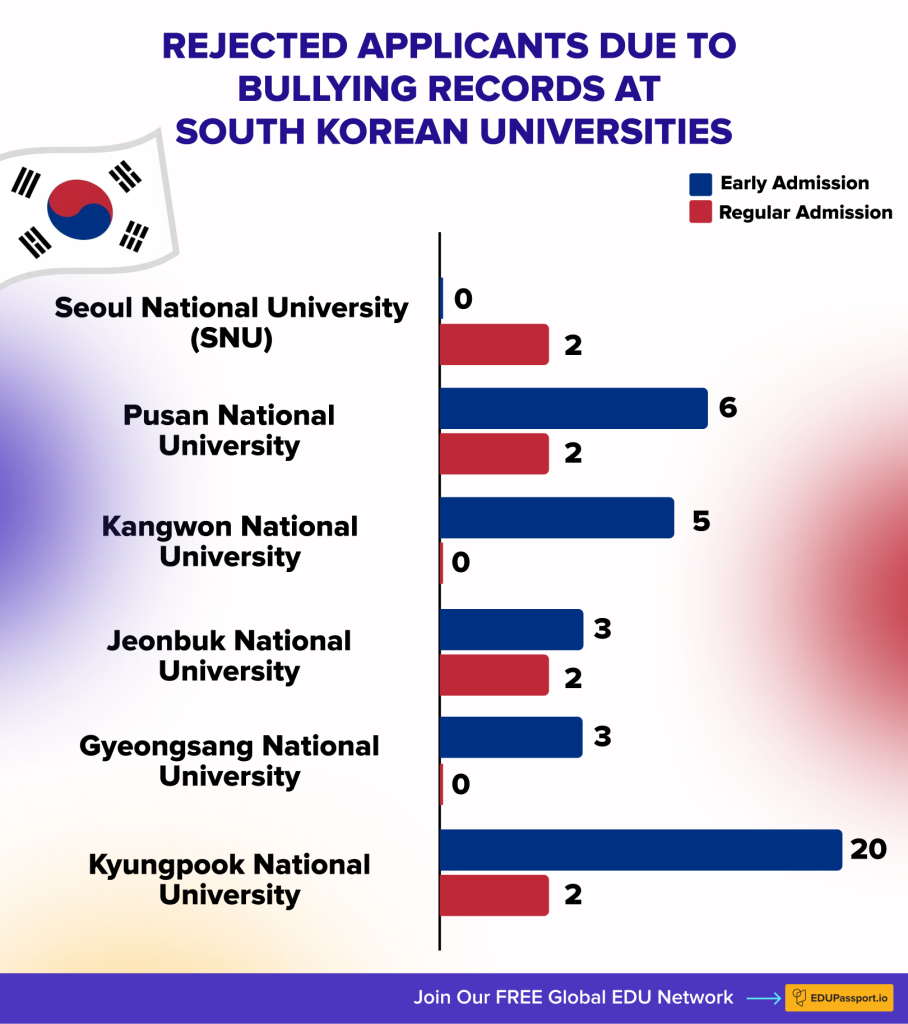

During the 2025 admissions cycle, 45 applicants across six major national universities were rejected due to histories of school violence. Among them were two students who applied to Seoul National University (SNU) with exemplary College Scholastic Ability Test (CSAT) scores yet were denied admission because of their past involvement in school bullying.

“At first glance, it seems shocking that high-achieving students would be turned away for something that happened years earlier,” says an education analyst. “But this policy reflects a broader societal push to emphasize character alongside academics.”

How Korea’s University Admissions Work

South Korean students apply to universities via two main routes:

- Early admission, which evaluates school grades, interviews, and extracurricular achievements.

- Regular admission, which primarily relies on CSAT scores, a high-stakes national exam known as suneung.

Historically, a student’s past disciplinary record had limited influence on their chances. However, SNU has been deducting up to two points from CSAT scores for applicants with serious school violence records, including disciplinary actions leading to school transfers or expulsions, since 2014. This year, those deductions became the deciding factor for the rejected students.

Other national universities also reported rejections based on bullying history:

- Pusan National University: 8 students (6 early admissions, 2 regular admissions)

- Kangwon National University: 5 early admissions

- Jeonbuk National University: 5 total cases

- Gyeongsang National University: 3 early admissions

- Kyungpook National University: 22 applicants, the highest among national universities

In contrast, Chonnam, Jeju, Chungnam, and Chungbuk National Universities did not reject students for bullying history because they only considered such records in limited admission tracks, like for student-athletes.

Policy Changes and Public Response

Starting next year, all universities in Korea will be required to deduct points or otherwise penalize applicants with school violence records, regardless of the admission track. The policy aims to prevent cases like the son of former prosecutor Chung Sun-sin, who had a history of bullying but was admitted to SNU with minimal consequences. Public outcry over such cases accelerated the expansion of these rules.

School violence in Korea is categorized on a scale from Level 1 (written apology) to Level 9 (expulsion). While minor incidents may be resolved quietly, serious violations (Level 6 and above) are now permanently recorded and impact college admissions.

Legal and Social Implications

As the policy expands, experts warn of a rise in disputes. Increasingly, students accused of bullying are hiring lawyers and filing administrative lawsuits to contest disciplinary decisions. Critics argue that law firms may profit from these conflicts, turning school violence into legal battles and disrupting classroom environments.

“This policy puts schools and families in a difficult position,” explains Dr. Lee Hye-jin, a child psychologist. “Universities are signaling that character matters as much as academics, but the legal and social ramifications are complex. Students, parents, and schools must navigate new pressures around accountability and fairness.”

Beyond Grades: A Shift in What Universities Value

In Korea, university admission is more than a gateway to education. A college degree is widely seen as a ticket to social mobility, job security, and lifelong status. By factoring in past bullying behavior, universities are sending a message: success is not just about grades, it is about who you are as a person.

While this approach may encourage better student behavior, it also raises questions about rehabilitation and second chances. How should past mistakes weigh against growth and maturity? And how can schools support students accused of bullying while maintaining accountability?

For educators, South Korea’s policy underscores the growing importance of character education alongside academic achievement. Schools are increasingly expected to balance discipline with guidance, teaching students the social and ethical skills that will follow them beyond the classroom. This focus on values echoes trends seen elsewhere in global education, such as in UAE public schools introducing daily noon prayers, where institutions blend curriculum with character and cultural education.

For educators, South Korea’s policy highlights a wider global shift: academic performance is no longer the only marker of readiness for higher education. Schools are being asked to balance discipline with meaningful guidance, helping students build the social and ethical skills they’ll carry far beyond their teenage years. This growing emphasis on values mirrors changes seen in other countries too. For example, some UAE public schools recently introduced daily noon prayers to reinforce character building and cultural identity, showing that education systems worldwide are weaving moral and community-focused learning into the school day.

If you’re an educator looking to explore best practices in fostering ethical, responsible, and academically successful students, you can register for EDU Passport and join a community sharing strategies and insights for classrooms around the world.

Takeaway for Educators

- Monitor how disciplinary records affect student opportunities.

- Encourage restorative practices alongside accountability in school communities.

- Recognize that university policies may reflect broader societal priorities around ethics and character.

- Learn from international examples of character-focused education, from South Korea to the UAE.

Source: Korea JoongAng Daily, NDTV